[title subtitle=”words: Marla Cantrell

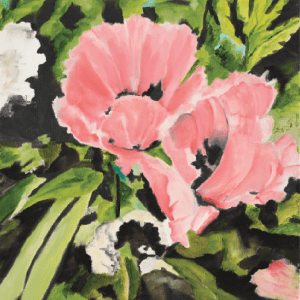

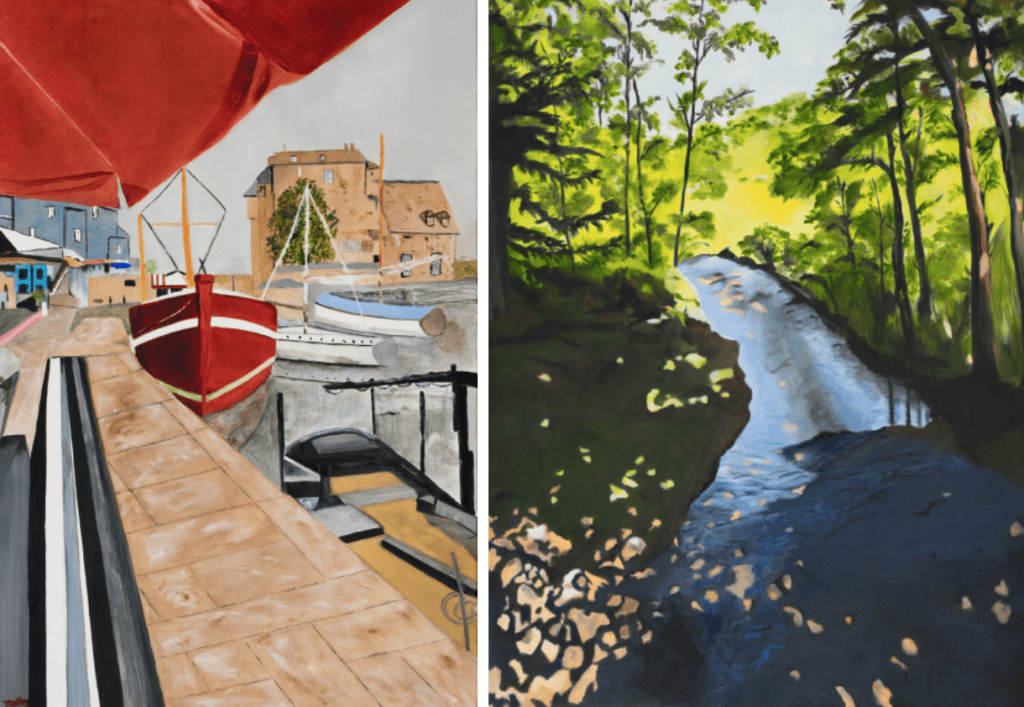

images: courtesy Maggie Malloy”][/title]

On a day in October that is more summer than fall, artist Maggie Malloy sits inside her studio at her home in Fort Smith, Arkansas. She works mostly in oil, which she says is more forgiving than other mediums, and starts the process of creating something beautiful. Her work is filled with emotion, with sights she’s seen on her travels, with a life overflowing with gratitude.

Each of her paintings is bright, bold and full of life. If she makes a mistake, she starts again. When things go wrong, that’s when Maggie gets going.

To understand her better, you have to go back to the late 1950s, stopping in Wewoka, Oklahoma, home to 6,753 people, including Maggie Malloy and her family. The town had boomed in the late 1920s after oil was discovered, its population swelling to 20,000. By the time Maggie’s father was working in the industry, things had evened out a bit, and Wewoka took on the rhythm of small-town America.

Maggie, a Catholic, was best friends with a Baptist pastor’s daughter, the two as close as sisters. Maggie’s mom was an RN, and played a mean hand of bridge.

Maggie might have ended up as a nurse as well, but an obstacle blocked her way. We’ll get to that later. For now, let’s go to the little hospital in Wewoka on Memorial Day 1958, when fourteen-year-old Maggie showed up as a brand-new nurse’s aide, dressed in a white starched blouse and skirt.

Maggie might have ended up as a nurse as well, but an obstacle blocked her way. We’ll get to that later. For now, let’s go to the little hospital in Wewoka on Memorial Day 1958, when fourteen-year-old Maggie showed up as a brand-new nurse’s aide, dressed in a white starched blouse and skirt.

During her first shift, two cars collided on one of the nearby roads, injuring seven people. At the same time, a teenage girl, the same age as Maggie, was in labor on the third floor. Since the girl’s life was not hanging in the balance, Maggie was assigned to her.

It didn’t take Maggie long to realize she needed backup. “Soon after I went to her room, I ran down three flights of stairs to ask Dr. Grimes what to do about her pain,” Maggie says. “He was smoking a cigar, and he said, around it, ‘Go time her contractions.’ My mother had given me her wristwatch that morning, with a second-hand, but I didn’t have a clue what to do.”

Maggie stared at her watch and tried to assure the mother-to-be. When Dr. Grimes came back to check, he told Maggie to go with him to the delivery room. As soon as the baby boy was delivered, he rushed back to the crash victims.

Maggie tells the story with such details that make you see her in the hospital, a silver wristwatch on her slender wrist, the beads of perspiration building on her forehead, her heart a drum. “That was the best acting job I ever did,” she says, speaking of her relative calm. Just after she says that, in a much more serious tone, she adds, “I felt like I became an adult that day.”

Maggie continued working at the hospital, and Dr. Grimes encouraged her to go into nursing. When she graduated, she decided to try journalism instead, at Oklahoma State. She married at eighteen and moved with her then-husband to Jacksonville, Florida, where she realized she really did want to be a nurse. But when she tried to apply, they politely told her they didn’t take married students.

Maggie went back home, set up her house, and at twenty had her daughter, Carrie, and later a son, Jeff. Her life became PTA and homework and volunteering.

1983 found Maggie in Fort Smith, Arkansas, at a volunteer training program for a hospice program, a new concept at the time, at Mercy Medical Center. She was soon hired as the volunteer coordinator, and worked with 395 families in her six and a half years there, wrote a book to help others manage volunteers for hospice programs, and fell in love with the community.

Her next step was with the Phillips Cancer Support House, which became the Donald W Reynolds Cancer Support House, helping implement another new idea: wellness and nutrition. From there, she began the Volunteer Connection for the city. When funds were cut in 2000, she became the Executive Director of the Bost Foundation.

Maggie became the go-to person in town. If you needed to know how to recruit volunteers, she could tell you. If you needed to raise money, she’d show you how.

During these years, she bought a lot of Arkansas artists’ work. While she loved the pieces, she didn’t have time to consider painting herself. But sixty happened to her, and she decided it was time. Never one to do things halfway, she soon had a studio built at her home.

With a studio, it’s a lot harder to put down your brush, and Maggie worked diligently. She served as team art advisor for Art on the Border, an annual local art show that showcases the great talent in our area. Her first commission was bought by her dear friend, Audrey, who wanted a Monet-like painting. Maggie charged her one hundred dollars, and the painting still hangs above Audrey’s couch.

Maggie took classes, first with local artist Julie Mayser, who gave her the support she needed, and then with Ann Griffin at Hobby Lobby, where she continued to grow. A class from Chris Verner of McAlester, Oklahoma, taught Maggie things about color she never knew she didn’t know. Chris was the color expert for Sherwin Williams, a title that says it all.

Art is a thing in motion, something that takes her out of her surroundings and onto the canvas. She recalls a day when she finally looked up at the clock and realized she was late picking her grandchildren up. She rushed to Immaculate Conception School with a wave of apologies, but her oldest grandson told her not to worry. When she said she’d set an alarm next time, he told her not to, worrying the sound would cause her brush to shoot across her perfect painting, ruining it.

As Maggie talks, she is wearing a top that’s multicolored, hoping it doesn’t show the paint that’s surely splattered there. She mentions trips to France to see the asylum where Van Gogh painted, to Monet’s garden at Giverny, and the scuba diving and sailing she’s done in Key West, the Bahamas, and the British Virgin Islands with friends as adventurous as she is.

On December 1 and 2, she and twenty-four-year-old photographer Joseph Barry, owner of the Train Museum on Garrison Avenue, will have a show downtown called Art in Motion. It’s Joseph’s first show, and Maggie is thrilled to be with him.

Joseph is one of Maggie’s posse of friends. She collects them like charms on a bracelet and treats them like gold. She laughs at the way she met most of them, through her work with non-profits that always needed money. She learned early how to ask. She talks about Butch Edwards, of Edwards Funeral Home, who once said, “The portrait they’ll use at your funeral will be one of you with your hand out.”

Maggie laughs. “I’m amazed I have any friends left in this town since I’ve asked so much of them.” Her friends who wouldn’t want to know a world without Maggie, would surely disagree.

Art in Motion

Maggie Malloy and Joseph Barry Art Show

914 Garrison Avenue

December 1 and 2 from 1-5pm