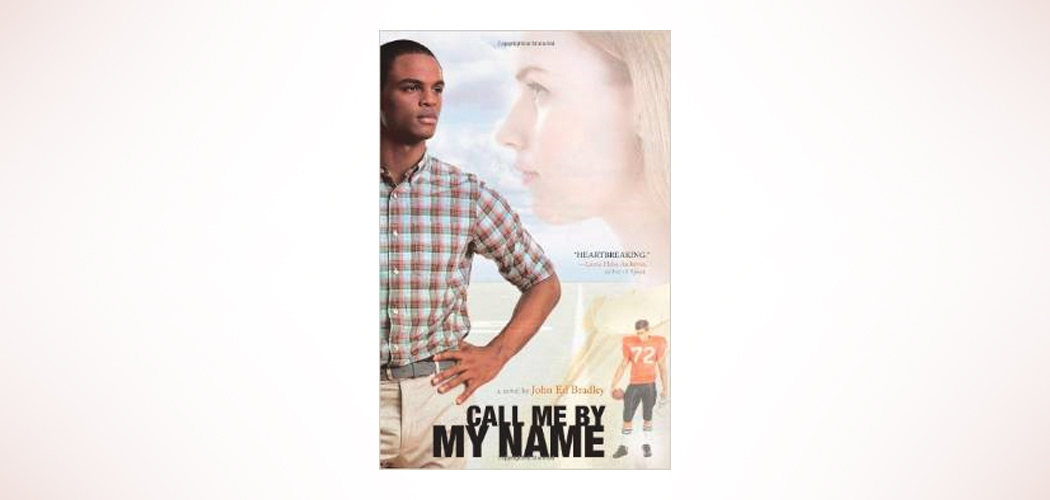

[title subtitle=”review Thomas Cochran”][/title]

By John Ed Bradley,

Atheneum Books for Young Readers, 265 pages: $17.99

Integration came hard to the Deep South in the early 1970s, the period John Ed Bradley examines in Call Me by My Name, his seventh novel. The transition was particularly rough in Louisiana, which provides the book’s rich setting. Rodney Boulet and Tater Henry are outstanding athletes who form a close friendship though they come from opposite sides of an un-named town based on Opelousas, where Bradley grew up. As an offensive lineman, Rodney is often responsible for his quarterback’s safety. He is a protector, a role he assumes on Tater’s behalf the very first time they meet when the youngster is attacked by a group of Rodney’s friends after he shows up in the town’s all-white park to play baseball.

Among those who favor strict segregation is Rodney’s father Pops, a man so racist he claims to be able to tell whether a pecan was picked by a white person or a black person. Naturally, he thinks that the “white” pecan should fetch a higher price. This is a world where black players are not quarterbacks, but Tater’s talent is such that his coaches finally recognize that they have no choice in the matter.

The growing relationship between Tater and Rodney’s twin sister Angie eventually forces Rodney into a reckoning with himself. A superb swimmer with an artist’s eye, Angie is sweet and smart. She is also “a person people automatically liked just because of how she looked,” Rodney observes, noting sadly that Tater is a person some people automatically despise for the same reason.

Tater and Angie begin to see each other regularly — at school, visiting Tater’s mother in the facility where she lives (the result of a violent confrontation with Tater’s father), and meeting in the park where Rodney protected Tater when they were boys. Inevitably, they are confronted by a group intent on doing them serious harm.

Rodney eventually faces his true attitude about race and is surprised to find that he is less like his tolerant mother than his intolerant father. The issue comes to a head when Rodney and Tater have an on-field confrontation about how far Tater and Angie may have taken their relationship. Like Angie, Tater tends to remain calm regardless of circumstances. He shows only occasional flashes of negative emotion, as when he sees the headline A STAR IS BORN: BLACK QB EXCITES IN DEFEAT and wonders if a player of Chinese or Native American ancestry would be so pointedly designated. Tater would rather be called, he says, by his name.

True to form, he responds to Rodney’s angry concern not with a verbal outburst but by simply throwing two passes at his lineman’s head. Later he says, “I might not be good enough for your sister, but it’s not because I’m black. I’m not good enough because she’s Angie, do you hear me?”

Having struggled for two seasons, the team coalesces behind the senior leadership of Rodney and Tater, whose outstanding play draws the attention of college scouts from across the country. Tater’s dream is to become the first black quarterback at LSU, and Rodney helps him toward making this a reality by staking his own dream of playing for the Fighting Tigers on a promise from the LSU coach that his friend will sign as a QB, not as an “athlete.”

In the poignant final chapter of Call Me by My Name the middle-aged Rodney looks back at how things turned out. Prone to brooding reflection as a teenager, he is now deeply haunted by the events of his youth that shaped him. He is celebrated as a good man who has achieved the pinnacle of success, but by his own measure he is lacking, his ability to protect others limited.

We have come a certain distance in our dealings with each other during the years since the integration of our public schools. Plainly we have a good deal further to go, a good many problems left to solve. So we take the next step and the one after that. John Ed Bradley has given us a story that reminds us of where we’ve been and inspires us to keep moving forward.