[title subtitle=”words: Tom Wing, Historian

image: courtesy of Tom Wing via the Fort Smith National Historic Site and the Western History Collection at the University of Oklahoma Libraries “][/title]

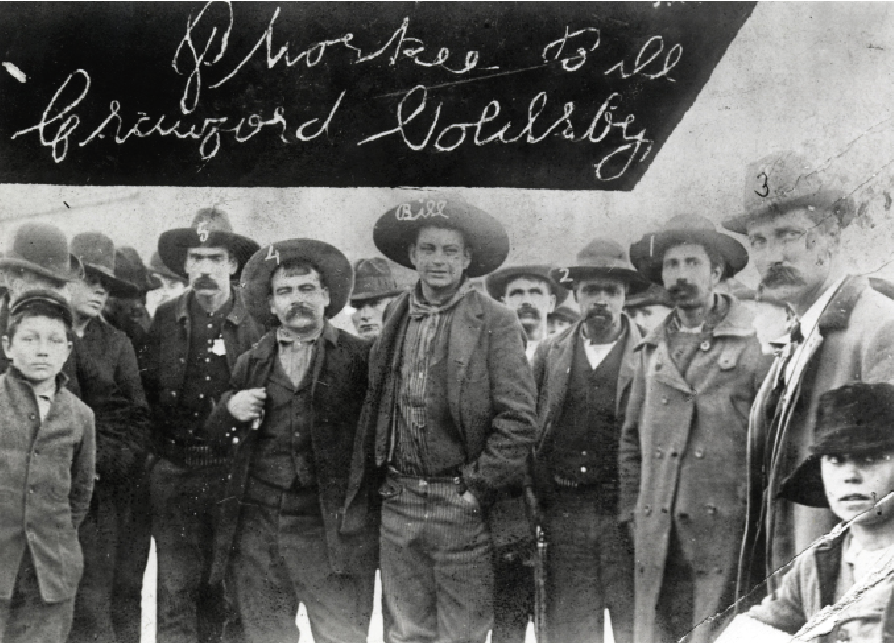

This month’s lesson begins with a photograph and a story that involves justice and injustice, murder, robbery, and judgment. The photo is of notorious outlaw Crawford Goldsby, aka “Cherokee Bill,” and includes the U.S. Deputy Marshals who transported him to Fort Smith, Arkansas. Goldsby’s criminal record included multiple train and bank robberies that resulted in the deaths of seven innocent victims.

In the iconic photograph, a few feet to Goldsby’s left is Isaac (Ike) Rogers (number 1 in the above photo), the man most responsible for his capture and the focus of our lesson. Taken at Wagoner, west of Fort Smith, and snapped seconds before Goldsby tried to escape, the photograph looks more like a reunion of friends. Photographs taken later show the outlaw in cuffs and leg irons.

The story starts like this: At the suggestion of U.S. Deputy Marshal Bill Smith, former Deputy Marshal Ike Rogers developed a scheme to capture the outlaw. Using his home and niece, a romantic interest of Goldsby’s, as bait, the ruffian entered the trap but remained on guard throughout a night of drinking and gambling that took priority over the girl. Rogers’ only chance came when the outlaw crouched by the fire to light a cigarette. A fierce and desperate struggle resulted, and Rogers, with the help of friend Clint Scales, disarmed and handcuffed Goldsby. Rogers and Scales then took the outlaw from Rogers’ home near Nowata, to the train station at Wagoner for transfer to Fort Smith.

Goldsby’s mother employed Judge Parker’s archenemy, J. Warren Reed, to defend her son in Parker’s courtroom. Reed, a law school graduate, frequently challenged the self-taught, “log cabin” methods of Parker, successfully overturning a significant number of cases on appeal. Goldsby’s lengthy trial allowed Reed to appeal to President Cleveland. While awaiting an answer, the outlaw used a smuggled pistol and killed jailer Larry Keating. This allowed prosecutors to focus on a murder case they could more easily win. March 17, 1896, Crawford Goldsby was executed on the gallows at Fort Smith for the murder of Keating.

Much has been written about the jail, trials, and executions at Fort Smith. Hell on the Border is considered an authoritative account. S.W. Harmon, the author, served once as a jurist and enjoyed the help of none other than J. Warren Reed to chronicle the story. Harmon lays a hard hand on Ike Rogers in the book, calling him “dastardly” and “a foul betrayer.” Harmon devoted a whole chapter to slandering Rogers’ character while claiming Cherokee Bill’s honorable friendship and financial support to Rogers. Harmon claims that Rogers was unable to support his own family and needed the outlaw’s help. Harmon openly justifies vengeance-seeking Clarence Goldsby (Crawford’s younger brother) and his stalking, threatening, and eventual murder of Ike Rogers.

J. Warren Reed’s failure to free the elder Goldsby surely influenced Harmon’s troublesome account of the murder of a former U.S. Deputy Marshal by the brother of the outlaw. We may never know the exact motivations and feelings on both sides of this story, but we do know that Clarence Goldsby shot Ike Rogers in the back of the neck, from behind, after he stepped off the train at Fort Gibson. Clarence fired three more shots into Rogers as he lay on the platform, and reclaimed his brother’s Winchester Ike carried.

Fast forward to today. Nicka Smith is a professional photographer and genealogist. Through oral history, Civil War Pension Records, Cherokee Roll documents, and DNA, she has traced her ancestry back to her great, great, grandfather, Isaac “Ike” Rogers. Her research and findings are incredible and have particular relevance today, as on August 30, 2017, the Supreme Court ruled Nicka, and other descendants of Cherokee Freedmen, as tribal members.

With an ancestry beginning through DNA in West Africa, Nicka’s family was enslaved by Cherokees and migrated west during the “so-called” voluntary removal period. A few generations later, Ike Rogers escaped slavery in the Cherokee Nation, fled to Kansas, joining the 1st Kansas Colored Infantry.

One of the first black regiments to be organized and see combat, the regiment defended Fort Smith from Confederate attack in 1864. Following the war, Rogers took his family back to the Cherokee Nation, where according to Nicka Smith, Rogers said, “My cousin told me not to come here to live, I told him, ‘You have schools here, and my children have Cherokee blood in their veins and have a right to attend them.’”

Rogers’ move back to the Cherokee Nation was pivotal in all that followed. S.W. Harmon’s allegations aside, Isaac Rogers, the man who apprehended THE most notorious outlaw in the history of Indian Territory, perhaps, deserves a little more recognition.

In the “Fort Smith School,” I’d like to offer Rogers that recognition. Ike was an escaped slave, who served his country, fighting for his freedom and the freedom of his people. Later, he served as a Federal Law Enforcement Officer. But even more than that, he was remembered by his family as a caring father, which is quite possibly the best reward any man can hope to garner.

More information on Nicka Smith’s amazing research can be found at: whoisnickasmith.com.