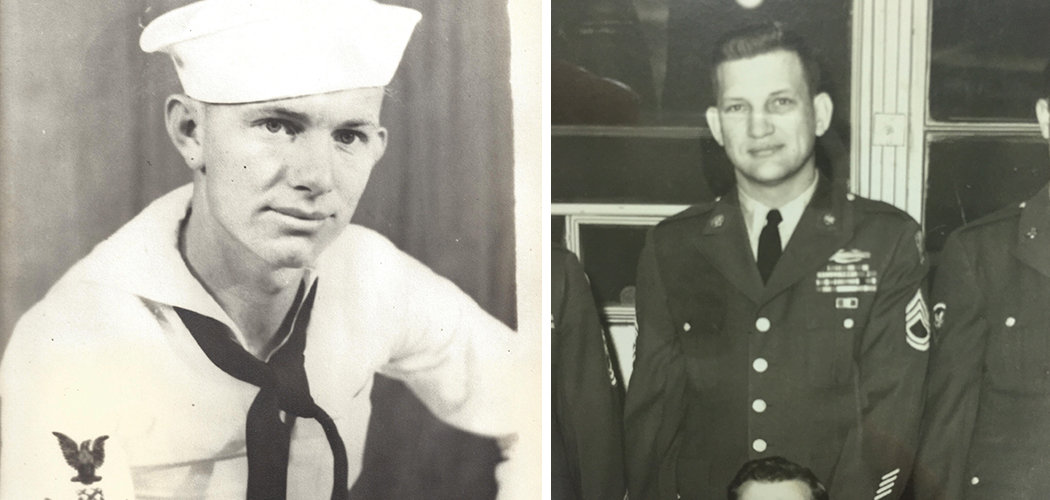

[title subtitle=”words: Marla Cantrell

images:courtesy Harold Mainer and Henry “Hank” Hauser”][/title]

Sixteen million Americans served in World War II. Only 855,070 are left today, most in their nineties, and Arkansas is home to 11,070 of them. Two of those veterans, Harold Mainer and Henry “Hank” Hauser, live in Charleston, Arkansas. One served in the Navy, one in the Army, and both witnessed pivotal moments in the deadliest conflict in world history.

They are remarkable men, with sharp memories and impeccable manners. Most days, they start their mornings at a local coffee shop, for breakfast and to catch up with their close circle of friends. At around eleven o’clock, they drive to Charleston’s Senior Center, where they eat lunch and play games like Rook. When asked, they can recall in vivid detail the battles they fought, the friends they lost, and the impact it had on their young lives.

HAROLD’S STORY

The world was a perilous place in 1941. Just two years before, Germany, under the rule of Adolf Hitler, invaded Poland. France and the United Kingdom then declared war against Germany, and Germany formed an alliance with Italy and Japan.

When December arrived, the U.S. was on high alert, although we had not yet entered the war. We were, however, supporting Great Britain’s efforts against the Nazis, and President Franklin Roosevelt was pressuring Japan to back off from its military expansion in Asia and the Pacific.

All of this mattered immensely to Harold Mainer, who had joined the Navy in October 1940 when he was nineteen, just as the draft was being instated. Soon after, he left his home in Paris, Arkansas, finished boot camp, and landed on the island of Oahu, just west of Honolulu. There, on December 16 of the same year, he stepped foot on a warship, the USS Helena CL-50.

For the next year, he trained hard and made friends. When he awoke on December 7, 1941, he planned to go ashore to celebrate one of his shipmate’s birthdays. Harold had twelve dollars and fifty cents in his pocket, and the sky was the blue of heaven, with clouds drifting by. “I had breakfast at 7:30 and after that I went topside,” Harold says. “All of a sudden three bombs hit. One hit the water. One hit the runway of Ford Island. One hit the hangar deck on Ford Island.”

The Japanese Imperial Navy was attacking. They had planned well: the cloud cover let them slip in, and since it was Sunday, many of the ships were in the harbor, giving them ample targets. It was a crippling assault, with 353 Japanese fighter planes, bombers, and torpedo planes launched from six aircraft carriers. When the two waves of attacks ended, 2,403 Americans were dead. Another 1,178 were injured.

“We got torpedoed. A ship next to us, a wooden-hulled minelayer, took the concussion from the torpedo that hit us, and it sank her,” Harold says. “We lost thirty-five men. I knew several of them.” He adjusts his glasses, and then says, “I washed my best buddy, Chance, off the ship with a hydrant hose. Shrapnel hit him and splattered him on the barbette [an armored cylinder for protecting the lower part of a turret on a warship].

“When I dropped out onto the deck, I was told by Chuck, ‘Go wash him off the deck.’ And I said, ‘Who is it?’ and Chuck said, ‘It’s none of your business. Do as you’re told.’ But nobody could shine a pair of shoes like my best buddy, and as I was washing it off, I seen one of his shiny shoes floating down the aisle. I ran to Chuck and I said, ‘It was Chance, wasn’t it?’ He said, ‘Yeah, but get busy.'”

Harold, now ninety-three, is a stoic man. “You do what you have to do and you move on,” he says. “We were trying to get the guys that were burned off the ship and to the hospital. There was about fifty injured. I didn’t have time to be scared.”

Along with the horrific death toll, there was major damage to the fleet. All eight Navy battleships were damaged, four of them so badly they sank. Three cruisers, three destroyers, one minelayer, and an anti-aircraft training ship also sank, and 188 aircraft were destroyed.

The attack was the final straw for America. The following day the U.S. declared war on Japan.

“The USS Helena was taken to the shipyard for repairs, and two months later, we were out to sea,” Harold says. “It was battle after battle, after that.”

Harold served on both the USS Helena and the USS Munsee, and brought home the World War II Medal and the Good Conduct Medal. He was part of the effort to pick up the WASP (amphibious assault ship) survivors from the Battle of Iwo Jima on February 23, 1945, and what he remembers most is that the sky lit up like a fireworks show, in part due to the flame throwers the U.S. was using.

During the fighting in Okinawa, he had a near-miss. His ship, the USS Munsee, was towing the USS Houston, after it had been disabled. “One of them suicide planes missed me by about 200 yards. He dipped his wings and spun away from the ship instead of into it.” On another harrowing day, Harold also spent four hours holding onto a raft, with thirty-five shipmates, after a torpedo attack broke the ship’s keel.

When the war ended, Harold, a Boatswain’s Mate First Class, was in Guam, loading ships with ammunition for a planned landing in Tokyo. “I was on a tug boat. I reached up and pulled the big horn. The guy above me hollered, ‘Hey! You can’t do that.’ And I said, ‘I spent forty-nine months over here. I think I can!’ And I pulled the horn again.

HANK’S STORY

On a map, Biak Island, on the western end of New Guinea, looks like a high-arched, high-topped shoe. It was there, in May 1944, that Henry “Hank” Hauser faced one of the bloodiest battles of World War II, as part of the U.S. Army’s 41st Infantry Division. He’d been drafted two years before, and had traveled from his hometown in Indiana to Australia for intensive training.

Hank, now ninety-two, talks about his role in the fighting. He’s the recipient of a Bronze Star and a Combat Infantry Badge. On the battlefield, he says, fear takes a backseat to staying alive. Your mind works at super speed, trying to figure out what to do next, and how to stay alive.

This tactic served him well. The conflict, called the Bloody Battle of Biak, began in May and lasted until August 17. The Japanese Army was defeated, but at a high cost. The U.S. suffered nearly 3,000 casualties, with 474 killed and 2,428 wounded. Still, it was far less than the Japanese toll of 6,100 dead and 4,000 missing.

What Hank saw during his days in World War II troubles him even today. What he saw, and the things he witnessed are worse than any plot from any horror movie you may have seen.

In August 1945, the U.S. dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan, killing 129,000 people. Hank was one of the soldiers who entered the city of Hiroshima approximately a month following the attack, just a month before he was scheduled to go home. “They warned us there’d be radiation, and they didn’t have equipment or masks for us,” Hank says. “We went of our own accord, and I was there three different times. It was absolutely horrible.” Hank turns the palm of his hand over. “One building looked like it just laid down. There was tile on it—kind of like Spanish tile, I thought—and when I reached out and got ahold of a corner, to lift it up, it disintegrated like a cigarette ash. You could see other buildings with just the steel structure left, twisted, like they were taffy that had been pulled.”

On September 2, 1945, the Japanese signed a surrender document, officially ending World War II. Hank, a Private First Class, thought he had had enough of war, but two years and seven months later, he went back in and spent twenty-one years serving his country. “The government paid for my pilot training,” he says. “I made a career of the military.”

It has been two hours since Hank and Harold sat down to

recall their time in World War II. When asked how they escaped the bad memories, Harold says he “kindly shut all that off and didn’t dwell.” Hank says when he got home he said he’d never go back. He stops, rubs his knee, and then says, “But I did go back, and all on my own this time.

“I realized the good Lord was going to carry me through. And He still takes care of me to this day.”

The two rise to leave. It is not as easy to get moving as it used to be, but they do all right. As they head to their vehicles, Hank says, “I’m going to fly over Charleston when I turn ninety-five. I’m really looking forward to that,” and Harold laughs, takes out his keys and heads to his pickup. On the front is a tag that reads, Pearl Harbor Survivor. He opens the door, turns to wave, and the two are off again, headed for home.