[title subtitle=”words: Tom Wing, Historian and Author

images: courtesy Fort Smith Museum of History “][/title]

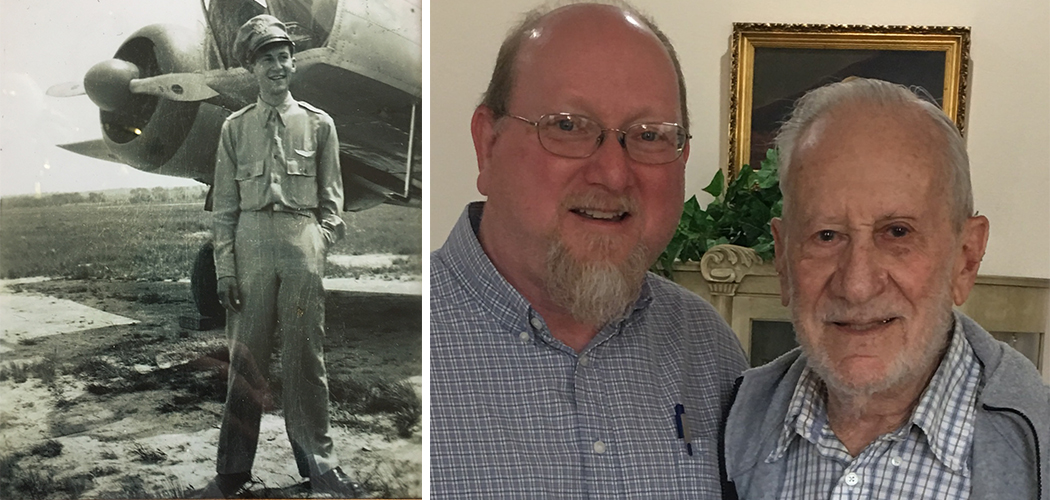

During WWII, the most widespread war in history, approximately 16 million Americans served in the military. It is crucial we hear the stories of those who served and to record those stories so that we’ll never forget all that was done on our behalf. Recently, I had the pleasure of sitting down with Irvin Sternberg to hear his story.

Irvin Sternberg, whose father owned a dental practice, was born in 1921, graduated from Fort Smith High School, and due to a sister living in Stockton, California, attended the University of California at Berkley, majoring in Commerce (business). He graduated in the spring of 1941 and returned to Fort Smith, working as a timekeeper at the newly created Camp Chaffee. On December 7, 1941, the Japanese attacked the U.S. Naval Base at Pearl Harbor, which ushered the U.S. into World War II.

Just weeks later, in January 1942, the Army Air Corps Exam Board came to Fort Smith. Irvin was one of thirty chosen to test, and one of thirteen who made the cut. The oral, physical, and written exams were given in the basement of the downtown post office, known today as the Isaac C. Parker Federal Building. At this point, Irvin had no idea if his assignment would be combat, training, or logistics.

Irvin was given a week to settle his affairs before leaving the Kansas City Southern Station in Fort Smith for Higley, Arizona. From Higley, later known as Williams Air Force Base, Irvin was transferred to Santa Ana, California, a newly built airfield Irvin described as “a sea of mud” for Cadet Training. He still remembers rifle calisthenics every morning in the dark, something he didn’t see much value in for pilots. Upon graduating as a cadet, Irvin’s pay raised from sixteen dollars to seventy-five a month. He took basic flight training in a PT-17 Stearman Biplane and learned basic flight maneuvers such as stalls, spins, loops, lazy eights, and the Immelmann, named for a German WWI pilot. He marveled that he had to speak with his training pilot, in the staggered cockpit, through a rubber hose. From there, he trained in the more complicated BT-13 Valiant, a fixed landing gear monoplane. For the first time, Irvin flew at night.

Next, he flew the T-6 Texan practicing gunnery. Irvin described his instructor for this part of his training as a “strict taskmaster” who unexpectedly took the pilots on an unauthorized flight over and through the Grand Canyon, a reward for finishing their training. He was promoted to Second Lieutenant and received his wings. He also got married about this time to Jean. They were married for fifty-two years at the time of her passing. When he carefully showed me Jean’s picture, his great love for her seemed to fill the room.

Fully trained as a pilot, he was assigned to fly a Beechcraft AT-11, a cargo/passenger plane equipped with remote doors in the floor serving as a bomb bay. Irvin’s job was to fly the plane while bombardier trainees practiced with the top-secret Norden Bomb Sight. The bomb sight allowed for high altitude accurate bombing of enemy targets far below. Irvin had to fly level and at a constant speed at 10,000 feet for the bombing practice, fighting wind, turbulence, and his own inexperience. The AT-11 could carry ten one-hundred-pound practice bombs. The bombardiers he practiced with later dropped real bombs on Japan and Germany during the war.

In mid-1944, Irvin was transferred to Waco, Texas, and assigned to test-fly repaired planes. During this time, he flew the iconic B-17, B-24, and P-38 fighter planes. He also logged some flying time in an AT-11, flying higher-ranking officers to their destinations. Required to make a long-distance flight once a year, Irvin went home with a fellow pilot to Detroit, and watched three games of the 1945 World Series between the Detroit Tigers and the Chicago Cubs, where he bought pennants for both teams.

The war with Germany ended in May 1945, and with Japan in August. A points system was implemented to send military personnel home. Those with combat experience received more points, of course. While many were sent home, Irvin remained in service and was transferred to Europe. He spent time in France, Germany, and Italy as a B-17 co-pilot. He even made a trip to Morocco and spent time in Casa Blanca, which in his words “appeared untouched by the war” in contrast to the devastated landscapes of the other locations where he was posted. Finally, in 1946, he had enough points to go home, arriving in the US first at Fort Dix, New Jersey before leaving the service at Fort Bragg in North Carolina. A train brought him home to Fort Smith just as one had taken him away in 1942. Irvin loved to fly, and in recent years, was treated to a ride in a restored B-17.

At ninety-seven years old, Irvin recalled the events told in this story as if they were yesterday. I marveled at his recall of details so vividly stored in his mind. I was thankful to be invited to sit beside him at his eastside Fort Smith home as he recounted this pivotal time in our history.