[title subtitle=”story: Marla Cantrell | images: courtesy Tanya Dedmon”][/title]

In 1944, when the world was at war, the draft found Austin “Skinny” Bell Swearingen. At eighteen, he’d seen little outside of Cecil, Arkansas, a town so small it was barely a dot on the map. He finished school, graduating from nearby Charleston High, and dreamed of college. He fancied himself a bit of a writer, penning poems, writing long letters, sometimes jokingly signing his name “Shakespeare.” Months after his draft notice came, he petitioned the University of Arkansas, working out a deal so he could study by correspondence no matter where Uncle Sam sent him.

But as he set out – first to Camp Robinson in Little Rock, and then to San Diego, and finally to sea – his heart always turned to home. He was one of six children, four boys and two girls. His two older brothers, Walter and George, were already serving in the Army. He’d watched his parents sit by the family’s one radio, a shadow crossing their faces as they listened for any news that might tell them something about their sons’ circumstances.

There was also a special girl, Betty Jean, a telephone operator in Fort Smith, and if time permitted, he believed a full blown romance might have blossomed. He loved his pop, and he worried after him – the hard work he did in the coal pits, the sorry condition of his teeth – but it was his mother, especially, that made his heart break. The thought of not sitting down with her, of not eating her fine cooking, of not sharing the harmless small town gossip that kept them chatting long after supper was over, seemed too much to bear.

Heading out, he knew he’d have to find a way to stay tethered to home. His letters started as soon as his feet hit Camp Robinson.

Aug. 3, 1944

Little Rock

Dear Folks, I arrived in Camp Robinson about 7:00 o’clock, and ate our supper. Then they took us to the barracks. As soon as they turned us loose we took out for the P.X. and bought postcards. There is six of us in each barrack. We won’t be inducted until tomorrow, we don’t know anything yet. I am lying on the floor writing this. I will write as soon as I can.

Love,

Skinny

Another postcard, written the following day, announced what he considered a grand piece of luck. He had been chosen by the Navy. Perhaps he thought the wide sea, the hulking ship, would be the things that kept him safe.

On August 5, he found time to write home again.

Dear Folks, I have been sworn into the Navy, and am leaving for San Diego at 9:00 this morning. We stayed in the Y.M.C.A. building last night.

He marveled at the train he rode. The Pullman car, the towns zipping by. He sat with his face pressed to the window, taking it all in, this land away from Arkansas, this world with deserts and palm trees.

Dear Folks, We passed about 50 yards from the Mexico border. We stopped in Yuma, Ariz. for a short time and there were some old Indian women sitting right flat down on the sidewalk selling beads and little trinkets. They couldn’t even speak English. They had the price of every article written on a little piece of paper that was attached to the article.

Once settled, he picked up his pen again.

San Diego Cal.

Aug. 9, 1944

Dear Folks, I arrived here in San Diego Tues. night about 11:30. We have been kicked and cussed around all day. We got our G.I. haircuts and we are all bald headed. We have been issued our clothing and equipment, and they have been trying to show us how to pack our bags, and make our beds, and confidentially it has been very boring. We will have to spend 12 weeks in boot camp, then maybe we will have it a little better. I guess you got all the cards I sent on the trip. .. Well, it is about time to start cleaning the bathrooms, guess I better quit scribbling. All the boys feel pretty badly, and pretty blue tonight, but maybe it will get better in a few days.

It only took Austin six short days to take out the life insurance policy he prayed would linger in a drawer inside his childhood home.

Dear Folks, I have taken out an insurance policy which I must send home, and also I forgot to send the receipt for my ration books. The lights go out in the barracks here at 8:30, and the recreation room is full so I am writing on a window sill, so don’t expect me to write too much. This insurance I took out is just like the one George has. I took out $10,000. If I get killed you and Pop will receive about $130.00 per month as long as you live.

He pushed on, doing his best work, learning to type, hoping he’d test high enough to become a radio operator or a radioman.

Not long after, Austin asked for pictures of everyone in the family. He asked his pop to wire money before his first leave, just in case he came up short. A round trip ticket will cost 44.00. I will have to eat on the train for about three days, so it will cost about 50.00. The church he attended – they all were required to go – could hold 3,000 people. He described the big ships, how he could see them in the channel from his spot in the barracks. I guess we will be seeing all the ships we want before long.

The typewriter he used cost ten cents for every thirty minutes of use. They have a slot in them just like a Nickelodeon only you have to insert a dime instead of a nickel. But Austin believed it was a good investment. If I get to go to radio school I will need typing so I am killing two birds with the same stone.

In September, Austin experienced one of the great wonders of California: Balboa Park in San Diego. They have the third largest zoo in this country out there, and it is a beautiful place. While we were out there we had our picture made by an old man who did his own developing. They aren’t good pictures but maybe you can tell what we look like in our uniforms. Incidentally both of my buddies are Arkies. They are swell guys too.

Back at camp, Austin studied hard, getting up at five in the morning, attending lectures all day. He was a smart guy, and his diligence paid off. He wrote home telling his folks he’d been chosen to be a radioman. His job was critical, working with a team that picked up radar signals and communications and transcribed them for the officers on board.

In early December, he wrote home telling his folks he’d gotten the gifts they’d sent. He’d also sent a suit to his little brother, Lawrence, and a coat to his mom. He joked, I want you and Pop to both get you some good clothes and step out once in a while. When I get out to sea and am made an admiral I am going to send you $100.00 and I want you to buy a bunch of new clothes and get out every now and then. I know you would really enjoy it, and don’t worry about we boys, we will make it OK when we get out. ..I sent to the University of Arkansas for a course in first year English. It just cost me $8.25 and I will receive three college hours for it just the same as if I were in college.

On December 12, he graduated from Radar Operators School. His diploma, no bigger than a half a sheet of notebook paper, brought him great joy. He sent it home to his folks for safekeeping. On the back he wrote, Some people may say I’m ignorant, cause I haven’t been to college, but just show them this. It will prove my knowledge. No doubt about it. This is the best rate there is, so you can say with pride, My boy is a radar man. Gee Wiz! He signed the note, Shakespeare.

The following day he moved eighteen miles from San Diego, to a place he called a distribution center. It was hot as heck in the day and cold at night, and the first night, before he was assigned a barracks, he slept in a “shack made out of cardboard.” He was given a physical, and was waiting to be shipped out. He thought he might go to Pearl Harbor, but he didn’t know. I hope Old Santa Claus is good to all of you this year, and you have a merry Christmas, he wrote. He signed the letter, Skinny.

Christmas Day, Austin ate in the mess hall, the food so good he sent the menu home. I didn’t mind Christmas like I thought I would. We were all in the same boat, so we just had a good time griping and raising heck. He then turned his attention to his brother, Lawrence, asking for a picture of him in the suit he’d given him. And he asked after his brother, George, who was in Belgium at the time. Mom! Have you heard from George lately? ..I have been a little worried about him since the German counter attack, but I guess he’s still alright.

The New Year dawned, and the world was still at war. Austin was now at a temporary camp in San Francisco, waiting still to be shipped out. He wrote home, talking about the lush land, the fat Holstein cows he’d seen, the beauty of the valley where the camp was. He signed the letter, Salty, and added, I now have a mustache and sideburns.

He must have been full of trepidation when he finally boarded the aircraft carrier, the USS Franklin, on January 13, 1945. The ship, nicknamed Big Ben, was thought by many to be invincible, a notion that comforted Austin. It weighed 21,000 tons, was 970 feet long, with an 880 feet long flight deck. The fuel tanks carried more than 200,000 gallons of gasoline for the 103 fighters, bombers and torpedo planes, and carried another 7,000 tons of oil for her own boilers. There were 3,500 people aboard. Their destination was the Pacific.

On January 28, he wrote home, trying to comfort his mother. I certainly hope George got his Christmas packages. Mom, I wouldn’t worry about him too much. I don’t think it will be long before he will be home again. But I don’t mind your telling me about it, if it makes you feel better to get it off your chest just go right ahead and don’t mind at all. I have been keeping up with the war news pretty well lately, and it sounds pretty good now. ..I will be going out before long now, and dog-gone it! you had better not start worrying about me. Do you think that after all the battles George and I survived when we were kids, we would be hurt in a little scrap like this?

In February, he apologized for not writing. He’d been in the sick bay for five days, reeling with a bout of tonsillitis and sea sickness. He wrote, Bye golly! if I don’t have a stack of letters from you, every time our mail barge pulls alongside, I am going to quit writing (ha). Another letter came at the end of the month. Austin hadn’t received mail for several days and he was aching for word from home. He signed off, saying he had the twelve to four overnight shift.

When March rolled in, the stress of battle was showing. He wrote, We had our first mail call in over a week, the first and I had been anticipating a great stack of mail, so when they sounded mail call I dashed up the ladder and began shuffling letters right and left. You can’t imagine how I felt when I couldn’t find a single one for me. I felt like I had been slapped in the face. But that night we got more mail aboard, and one of my buddies woke me up and gave me a letter from you, which tended to ameliorate my broken morale. Mom, I don’t want any of you to worry about me at all, but for goodness sake! please don’t forget to write. I can make it fine as long as I can be assured of getting a big stack of mail every time we have mail call. ..It is hard for anyone back home to realize how much a letter from home can mean to a man overseas. It makes him feel like someone still thinks of him, and cares what happens to him. It lessens the feeling that he is just a tramp, cast out miles from home to suffer the punishments of fate.

In his next letter, on March 14, he talks about the girl back home, Betty Jean Robertson. Mom, Betty Jean would like for you to let her know in the event anything happens to me. ..This may sound a little grim, but we may as well face facts. You can’t hide from life, or live in fear of death and be happy. But I am not worried about it. He ends the letter this way. I had rather have letters from you and Pop than anyone I have ever written to. I wish you were nineteen and I had met you before Pop did, but then I wouldn’t have such a swell Pop. He signs the letter, My sincere love, Austin Swearingen.

Just after seven in the morning on March 19, while the crew was eating breakfast, a Japanese Kamikaze pilot emerged from the clouds on a suicide mission. He headed right for the ship, dropping a 500 pound bomb on the flight deck. First-hand accounts say the bomb incinerated some of the men standing in the chow line and shot others straight into the sea. Floors buckled, crushing men between them, and trapping others in a cave of metal. Pipes burst, spilling fuel that caught fire. Smoke billowed, sirens sounded, and a ricochet of explosions quickly wiped out the Combat Information Center.

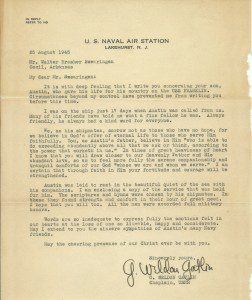

Not long after, a second bomb hit. The attack killed 724, and wounded another 265. The chaplain, who had been on board only seventeen days, was not injured. He grabbed a life jacket, a vial of holy water, and headed through the smoke toward the damage, giving last rites, and doing all he could to help the medical crew save others. His actions that day earned him the Medal of Honor.

The family of Austin “Skinny” Bell Swearingen never knew where he was when the bombs hit. Perhaps they heard the reports that made news across the globe, and prayed Austin had been spared. But by March 26, 1945, the last letters they’d written their son came back unopened, a terrible omen, and on April 5 they received the telegram that broke their hearts. Their dear boy had been buried at sea.

The letters, along with the Purple Heart, were gathered up and put away by Austin’s mother, who never stopped grieving. The letters Austin mailed in the U.S. were sent free of charge. Once on ship, Air Mail cost six cents. The stamps show the underbelly of a red plane that looks unstoppable on the tiny rectangle. The envelopes are now yellowed, and are marked by Austin’s mother, 2nd one from the ship, and so on, until the final letter, 6th and last one from the ship. The ink on some of the correspondence – each one began with the greeting Dear Folks – has faded so much it’s almost gone. The Western Union telegram has been laminated, as has the sermon preached for Austin, most likely well after his flag-draped body, probably weighted with a shell casing, was lowered into the sea.

There is no grave here, but Austin’s name is engraved on a monument at the Franklin County courthouse. When his family visits, they reach out and trace the letters. They think about this young boy who left on a bus to Little Rock and only returned once on leave. They think of his two brothers who made it back. They wonder what might have become of Austin if he’d been able to finish his degree, if he’d been able to survive the war. They wonder what it would have been like to see him spring up onto the porch of the folks’ little house, this tall, skinny boy. He would have called out, Mom, I’m home, and the celebration would have begun. It would have lasted well into the night and on into the inky hours of the morning.

[separator type=”thin”]

If you’d like to write to our military men and women, past and present, contact AMillionThanks.org. Groups, schoolchildren, and churches can also participate. The next deadline is January 15, for letters and cards for Valentine’s Day, 2014.