Part I of The Jimmy McGill Story was featured in our March 2022 issue. If you missed it, you can read it at DoSouthMagazine.com.

The world held the lowest of expectations for North Little Rock native Jimmy McGill and for nearly four decades of his life, he lived down to every single one of them. Criminal. Drug dealer. Gangbanger. Junkie. These labels worked their way under his skin like tattoos, as much about who he was raised to be than who he was, but one and the same to the naked eye witnessing the maelstrom of his life.

“I can remember cutting corners off bags and stealing them at twelve and thirteen years old, stealing methamphetamines from my dad,” he says. “He had these old cars behind my grandpa’s, so one time, I’m out there playing in these old cars, and I find this shaving bag. It’s literally got a pound of methamphetamine in it, rolled up into ounces.”

“So, I pulled out an ounce and I take a little out of each bag. I’ve got this cigarette cellophane filled up all the way across the bottom, like a quarter ounce. I sold it for two dollars thinking that it went the same that marijuana went for, you know? I knew one finger across the cellophane was a joint and a joint was two dollars. I treated the meth just like it was the same. That’s the environment I grew up in.”

In some ways, Jimmy was very good at what he did. Coming out of juvenile “training school” as a teen, he came home to North Little Rock and used his considerable leadership skills to organize the percolating gang scene. Jimmy stood out in this violent world having received a savage education while inside that transformed a picked-on eighth grader into a hair-trigger predator.

By many other measurements, Jimmy was really bad at what he did, especially after he started using heavily. The coup de grace was a Lonoke County deputy waking him up in 2014 from a drug-addled stupor behind the wheel of a running car loaded with ice and stolen property. Already a five-time loser, everyone including Jimmy, assumed he’d breathed the last free air he was going to for a long, long time.

He didn’t have the capacity to know then that God had been keeping tabs, watching over him in drug dens and generally providing the guardrails on a life careening out of control. And when the time came, the Lord used a myriad cast of characters to reveal to Jimmy the true plan He held for his life, making sense of the chaos.

It started with a sheriff tough enough to get the attention of a strung-out hard case.

“Here I am, Lonoke County jail and I’m a trash-talker. I’m a pretty entertaining guy,” Jimmy says. “The sheriff, John Staley, takes a liking to me. Now Sheriff Staley is a hard ass. He’s the old Doc Holliday, Wyatt Earp-type, but he was a good man. He never whooped me, but he was very hardcore. He believed in doing what was right and you owning responsibility.”

“One day, Sheriff says, ‘McGill, pack up. I’m going to move you up front.’ I’m like, ‘What? Move me up front?’ He takes me out of the back of the jail, puts me in the front and I become a trusty. I’m living good for being in jail.”

The gesture was impactful and approaching forty years of age, Jimmy started taking stock of his life. If a ramrod like Sheriff Staley could see something redeemable in him, well, who knows? Life began to look much different until one day an all-too-familiar devil paid him a visit.

“My cellmate gets this dope from a girl who’s going through intake,” he says. “He’s like, ‘Look what I got.’ I literally turned him down thirteen times a day, but he kept putting it in my face. I said no ‘til I couldn’t say no anymore.”

“That was the day. Looking back, I understand that was the first time I used against my will. I didn’t want to do it. Hated myself because I couldn’t not do it. But I did and the sheriff caught me. Locked me up in the hole and he had tears in his eyes as he did it, almost, over me betraying his trust.”

“But that was the right crack in the wall. Something about wanting to show him that I wasn’t the screw-up he thought I was, that’s what did it. I just hit seven years being clean in February.”

Jimmy’s next mooring point entered his life shortly thereafter. Now in a transitional program, he was at a recovery meeting when a brassy, tell-it-like-it-is woman named Chelsea came in and sat in the chair next to his.

“My living skills at that point were animalistic,” Jimmy says. “The majority of my addiction I’m like a frickin’ raccoon. I only come out at night. I think in my mind I’m the cutest thing in the world, but I look like a trash can. I’m thirty-eight years old with my hat on sideways, pants sagging, throwing gang signs. I’m clean, but my thinking is corrupted.”

“Chelsea starts talking to me in a fashion that no one since my dad has ever had the nerve to talk to me. She tells me, ‘You look like a freakin’ idiot. You need to fix your hat and pull your pants up. You look stupid.’ I didn’t know if I wanted to date her, fight her or marry her.”

“I was so intrigued. I only knew women who were in the grip of addiction. They’re not living by morals, they’re not outspoken, they don’t have convictions. The women I knew were prostitutes and thieves and they were the female version of me. All of a sudden, there’s this clean, educated, outspoken girl telling me what I need to hear that no one else had the gumption to do.”

Chelsea, two years clean when they met versus his nine months, straightened out his thinking, taught him how self-respect comes from giving respect to others. Most of all, she never let pity and self-loathing drive her back into dark, beckoning ditches. They married in 2017 and he still speaks of her as the life preserver she is.

“Chelsea ends up being this vessel that God really uses,” he says with a warm smile. “She’s had her job cut out for her.”

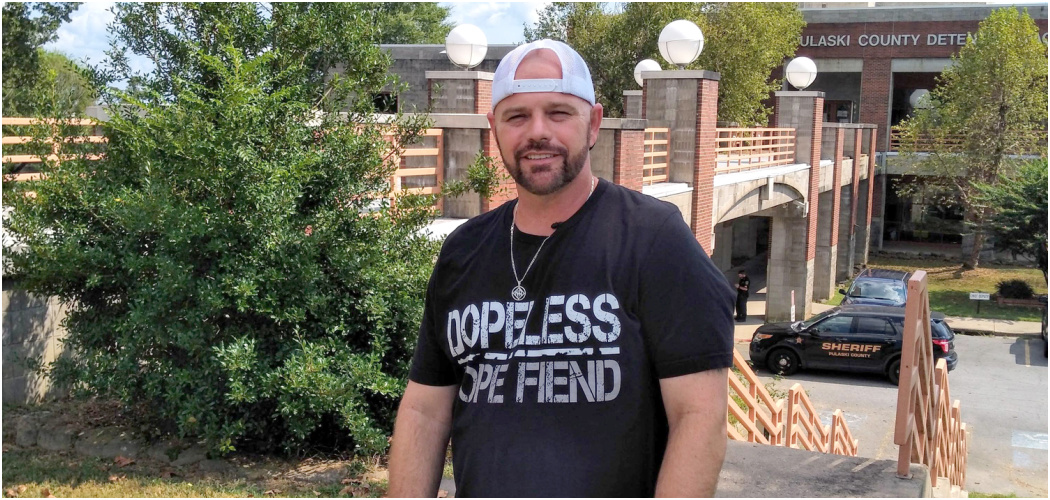

The third person who caps this incredible comeback story is Kirk Lane, now Arkansas Drug Director, who served in law enforcement in central Arkansas for thirty-five years. Kirk was well acquainted with the old Jimmy, having arrested him on multiple occasions. But Kirk also recognized the value of such life experiences in the new Jimmy, hiring him as the state’s Recovery Manager at Arkansas Department of Human Services. It was a move so bold, the hire needed Governor Asa Hutchinson’s signature given Jimmy’s record.

Jimmy has tackled his new role with evangelistic fervor. He wrangled $100,000 in funding for three pilot peer programs that put recovering addicts like himself within reach of those trying to get clean. Two programs – one called Exodus Life and one based in the Lonoke County Jail – were so successful the work is spreading to hospital emergency rooms, police departments and additional jails. More than four hundred peer recovery specialists have been trained on materials Jimmy developed. And he’s helped pull multiple states onto the same page to improve and expand publicly funded recovery programs throughout the region.

“It was a team effort, but there was no one to grab it by the horns and say, ‘This is the way we’re going to go.’ So that’s what I did,” he said. “I immediately identified leaders from the recovery community, and we sat down and built a model collaboratively that’s changing history and changing the trajectory of recovery services across the nation.”

Jimmy also found time to write a book on his life and is an in-demand public speaker for groups ranging from state legislators to inmates. Leaning heavily on faith though he does – he first found salvation in Lonoke solitary, devouring a stolen Bible daily – he tells them effort and commitment is what’s most needed to meet the problem of addiction in society. And the clock is ticking.

“There’s this constant fight whether addiction is a disease or not,” he says. “People will share their opinion like it’s fact. People in the faith community, they’re like, ‘Well, Jesus is the only way to go.’ I’ve seen people get clean for thirty years who don’t believe in God at all. That doesn’t mean God won’t use them in a powerful way. He used me at my worst.”

“Addiction is not a Black problem, a white problem; it’s not a gender problem. It’s a human problem. We as a people have to come together and build a better plan or we’re going to be going to three or four funerals a week, no matter who you are. And it’s easy to sit up on your high horse and judge until it’s your kid’s funeral. Right now, fentanyl is the number-one killer in America. I’m going to two or three funerals a week. It’s only a matter of time before the rest of society catches up. Then it’ll be put up or shut up.”

Jimmy glances out the window and watches people pass on an overcast morning. There was a time he sized people up as victims and in a way, he still does, looking for the telltale signs of addiction and trauma. It’s a parade without end, this line of the wounded and broken, and it chews up as many who try to help as it kills those needing it. For years, he laid at the bottom of that well, until bubbling grace lifted him to the surface, refreshing him daily for the work yet to be done.

“When I came home from my sixth trip to prison, if you would have told me I was coming home to become the first parolee with a state position, I would have thought you were cuckoo-bird crazy,” he says. “I wouldn’t have even understood what you were saying. But that’s what happened. God took me from a state prison and put me in a state position. Did the impossible. None of that would have happened without all those experiences and all those stories to tell.”

“God always meant for my gifts and abilities to be used. What the world wanted for bad, He used for Him.”

Follow Jimmy on Facebook (facebook.com/jimmymcgill76), his YouTube channel and on Instagram (jimmymcgilllive). Jimmy’s book, From Prison to Purpose can be found on Amazon, Barnes & Noble or wherever books are sold.