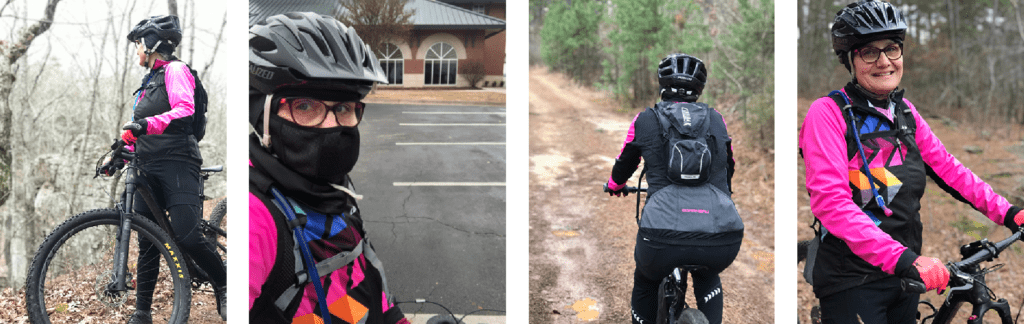

[title subtitle=”words: Marla Cantrell

image:courtesy Cheryl Hutchens-Perry”][/title]

On New Year’s Day, when fog rolled in and the temperature topped out at forty-five degrees, Cheryl Hutchens-Perry bundled up, put on her helmet and climbed on her gravel bike that she’d named Lilah. Her goal was to ride a forty-six-mile loop that would take her from her hometown in Alma, through Rudy, on roads that bank the Ozark National Forest, then Dyer, and finally home.

She’d taken up riding again on Memorial Day, 2018, after a family friend, Michael Wiseman, offered to help her. She’d bought a mountain bike from Phat Tire. “The first time, I thought I was going to have a heart attack and die. I was so out of breath,” Cheryl said. But they continued training, and Cheryl grew stronger.

As a child, Cheryl had been an avid rider in San Francisco, zipping around on a green Schwinn Sting Ray with a banana seat. At twelve, she moved from San Francisco to Alma. It was 1970 and Alma was a bit of a culture shock. At school she asked classmates where the town’s planetarium was, where the museums were. The town, whose population hovers around 5,700 today, was considerably smaller then.

Gradually, Cheryl found her own planetarium underneath the blue-black bowl of night sky. Museums were replaced by trips to ponds and streams where she observed fish and frogs, native grasses, the tumble of water rushing across rocks.

While she didn’t have the hills of San Francisco, she still rode, often to Van Buren, the next (slightly bigger) town over, where, in the summertime, she’d spend much of the day at the city pool.

While she was adjusting to small-town life, Tom Perry, a boy who would play a starring role in Cheryl’s life, was finding his footing as a brand-new resident of Van Buren.

One day, when Cheryl was visiting her cousin, she met Tom. On the surface, nothing much happened. But deep down, everything that mattered occurred in those few seconds. Cheryl took one look into Tom’s sky-blue eyes and felt more than her young mind could comprehend.

Tom felt it too, and soon they were burning up the phone lines. They were boyfriend and girlfriend long before Tom turned sixteen and took Cheryl on a proper date. “We had the same thoughts,” Cheryl said. “We’d finish each other’s sentences.”

On June 5, 1976, Cheryl Hutchins, age eighteen, a week after graduating from Alma High, married Tom Perry in her parents’ yard. That day, it rained, and Cheryl remembers feeling the weight of that, of worrying the day might be ruined.

It is said that rain on your wedding day is a sign of a good union, but Cheryl didn’t know that. All she knew was that her outdoor wedding was in jeopardy. But then, around five in the afternoon, the sun came out. The orange daylilies on the lawn all but glowed.

Guests sat in borrowed chairs on either side of the aisle, and Cheryl walked between them and into her grand, new life.

There were times, of course, when Tom and Cheryl’s fairytale was anything but. Sometimes money was tight. Sometimes their two big personalities clashed. But always they loved each other.

In 1987, Tom and Cheryl were parents to a son and daughter. Cheryl was an artist with a growing following, her sketches and paintings showing up in homes across the region and beyond. She’d also been in and out of nursing school, juggling motherhood, trying to make everything fit.

Tom, who was most at home surrounded by nature, loved the land and the plants that sprang from it. He’d worked as a stone mason, at a garden center, and in landscaping, and planned to have his own landscaping business one day. But something was going terribly wrong inside his body, and he eventually ended up in ICU.

He was diagnosed with hypersensitivity pneumonitis, often called farmer’s lung or birder’s lung because these groups are most likely to be exposed to certain offending organisms specific to working the land or with birds. The doctors told Cheryl that Tom would be an invalid, that he probably wouldn’t live very long.

“Tom looked at me from ICU with chest tubes in his body. He said, ‘Oh, don’t worry. I’m going to get better and we’re going to have our business.’ We lived in a trailer at the time, and he said, ’I’m going to build you that big house. And we’re going to have more babies.’”

He did everything he set out to do. They had two more children. They created Tom Perry Landscaping, which operates today in seven states. Their big house sits like a promise on their forty acres. Cheryl got her degree in nursing, and later enrolled at the University of Arkansas, in the Doctor of Nursing Practice program, working to become a Family Nurse Practioner.

In 2016, when Tom’s condition finally caught up with him, Cheryl put her schooling on hold, and stayed by his side, convincing him to try her preferred plant-based diet, a decision she believes gave him an extra year. But on March 26, 2018, Tom passed away.

Tom left this world gently, held by his big, caring family. They’d made a playlist for him, and as he passed from this plane to the next, his favorite song, “Gold Rush,” by Crosby, Sills, Nash & Young, played.

They’d talked a lot about death and dying, something Cheryl recommends for every couple. “In one of our conversations toward the end, he said, ‘You know, I wouldn’t change anything good or bad.’ He said, ‘I would want it to be just exactly the way it was.’”

Not having Tom beside her was heartbreaking, and she did her best to deal with the grief that followed her every step. When Cheryl was asked if she wanted to bike again, she understood how much she needed to ride.

Once, on a trip to the Sequoyah National Park, she’d stood beneath the towering wonder of her favorite tree, a giant named President, and she asked it for the secret to life. The answer she heard was “be still.”

As odd as it seems, it’s easier for her to be still while she’s in motion. Her mind and spirit settle down. As she peddles up a steep hill at three miles an hour, her only thought is getting to the top. As she sails down the other side at thirty-one miles-per-hour, she’s giddy with the feeling of freedom. In between, she thinks of a million things: rain on her wedding day, the first time she saw the love of her life whose eyes were the color of the bluest sky, the promises he made and kept.

The physicality of biking mirrors the process of working through grief. “These hills or waves of grief are so hard. You look around, and you think, I can’t get through. I can’t do it. You keep your head down and you just keep going, and you get past it, and then you’re like, I can do it. I’m capable of doing so. The next hill doesn’t look as intimidating and the next wave of grief doesn’t feel as powerful.”

On New Year’s Day, Cheryl stopped just short of her forty-six-mile goal. Dusk was falling and her bike, Lilah, didn’t have lights. It was fine, though. Her ride had given her what she needed. There’d been an incident with a dog that had left her shaken for a bit. But there’d also been a stop at a spot that seemed like the top of the world. If heaven could be more beautiful, she didn’t see how.

Since then, she’s been asked to ride along with Pandemonium Cycling, an all-female bike club and race team in Tulsa. Her childhood friend from Alma, Pamela Smith Mitchell, invited her, something that thrilled Cheryl.

One of the last requests Tom had was for Cheryl to “see everything.” She started with a ride on January first, past land she and Tom had seen a thousand times. She felt him beside her. She thinks she always will.