[title subtitle=”words: Evelyn Brown”]{ Reader Story }[/title]

All I really need to know I learned at Woolworth’s.

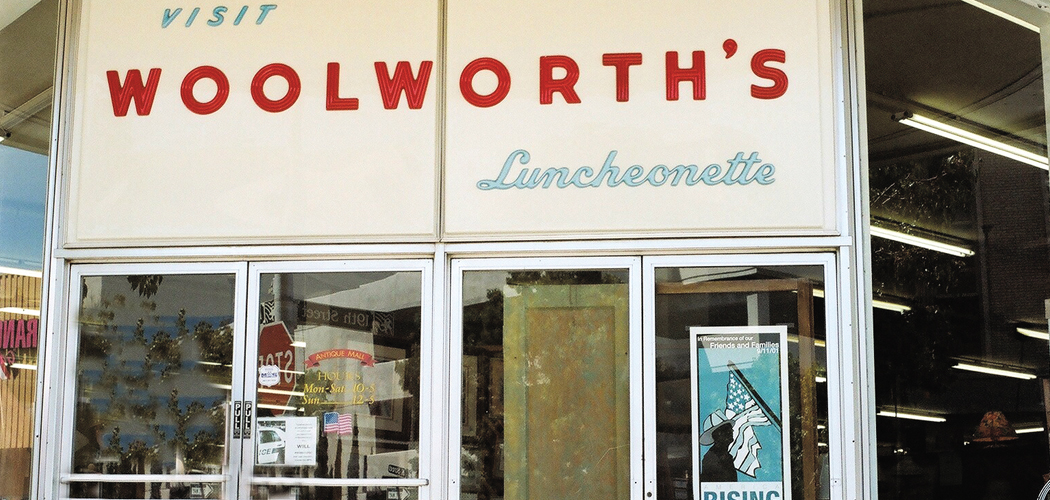

At age seventeen, I applied for my first job at Woolworth’s, one of the two five-and-dimes in Sand Springs, Oklahoma. The other was TG&Y, which lost a bunch of its customers to Woolworth’s when it started staying open on Sunday afternoon, a no-no in that Baptist-dominated community. The Baptists also would not condone school dances, so I didn’t learn to dance unti…well, really never. Which gets me back to my point — how I learned more working at Woolworth’s than I did in thirteen years of public education, including kindergarten — a point I made so many times to my children that they thought I had worked at Woolworth’s for most of my life before they came along.

My Woolworth’s education was delivered by Lillian Stottlemyre, who had been assistant manager of the Sand Springs store since it opened in 1959. I supposed she had worked at Woolworth’s all her life, but actually I knew nothing about Lillian Stottlemyre’s life. When she “interviewed” me in January 1963 — “Fill out this application. I’ll call you if we need you.” — she seemed to loom over me as I sat at the table in the employee lounge, looking down at me with gray-green eyes, smooth plump cheeks, curly steel-blue hair framing her flushed face. She was heavyset, we called it then, grandmotherly looking in a scowling sort of way. Did she have grandchildren? I don’t know. I never heard about grandchildren or children or husband or home. Lillian Stottlemyre did not discuss her private life with me. As far as I knew, she lived at Woolworth’s. Anytime I was there, she was there.

I started learning from Lil, as her name tag stated, from the moment I started to work, which as it turned out was the same day I applied. When I got home, she had already telephoned my mother to have me report back at six o’clock that very Saturday night. I would keep on learning from her for fifteen hours a week, more or less — all day Saturday and a couple of nights during the week — for the next year and a half.

When I went in, Lil looked me over head to foot. “You can’t wear those crew socks. You need nylons. Go back and get some off the shelf, and some garters to hold them up. We’ll charge them to your first pay envelope.” I never got a check from Woolworth’s. As with most places in those days, we were paid in cash, with deductions printed on the front of the envelope.

She handed me my smock, blue-green nylon trimmed with darker blue bias tape that lengthened into ties on each side, one size fits all. I practically had to double wrap the apron around my skinny torso; Lil’s was stretched to the limit around hers. “Woolworth’s” was embroidered in red script on the right side. Lil gave me my name tag with “Evelyn” printed on cardboard inserted into a plastic sleeve. I would eventually print those name tags for all the new hires and for those, including myself, who would wear them when they took their smocks home to wash — another requirement of employment — and forget to pin the name tag back on the left shoulder.

Lil taught me to run the printer. It’s funny to think about what we called a printer then. It consisted of a frame in which I would put wood or metal type — blocks with raised backward letters and numbers — ranging in size from maybe a quarter inch to three inches tall, depending on whether I was printing name tags, signs, or posters. I would roll ink which was the texture and consistency of heavy grease over the type, lay the paper over that and run another roller that would press the ink onto the card or poster. Yes, just like the way Benjamin Franklin printed Poor Richard’s Almanac, and, my kids believed, just about the same time.

I actually enjoyed doing that printing, after I got over my disappointment that I would not be a cashier like Judy Whittenberg, a cheerleader who was a year ahead of me in school and whom I dreamed of emulating. Lil tried to teach me to run the register, but I, who was in advanced math, could not make change. I counted money back to Lil just fine in our practice sessions, but in the heat of the moment, with the customer standing there complaining about having to pay four cents tax on the dollar, which I had to figure in my head because the registers of those days did not help even a little bit, I would invariably panic. The day I came up ten dollars short when I counted out my drawer was my last day of using the cash register.

Lil was optimistic in her way. “There are plenty of things you can do around here. We can always hire a cashier, but we need someone who can handle the other jobs.”

Lil’s way of teaching was to do a job as she explained it, and then have me do the job while she critiqued it. After that, I was on my own. So, as I told my children many years later, I learned to print signs, run the candy counter, make keys, cut shades, engrave jewelry, measure cloth, catch fish, set up displays, tag merchandise, do inventory, watch sidewalk sales, dust, straighten, fill out orders, unpack stock, handle layaways. Then I learned to redo all that when Lil found mistakes.

Lil probably thought she was the one who made the mistake when she decided to have me try to get customers to buy a potato peeler which was being stocked by the store for the first time. Her plan was for me to stand at a table near the front of the store and — you guessed it — peel potatoes to demonstrate what a marvelous job the device would do. That worked pretty well, once I got the hang of it, and a couple of people actually picked one up to buy. As I enthusiastically peeled, some of the skin shavings made their way to the floor. An elderly lady slipped on a potato peel and almost fell. “You’d better watch what you’re doing, young lady!” she huffed. Lil quickly closed down the demonstration and taught me how to clean the floor.

I remember advice Lil gave me: “Call me Lil,” she said when she hired me, but I was to call the manager Mr. Nelson — because he was the manager or because he was a man? — mostly because that’s what Lil told me to call him. “Always show your boss enough respect to call him ‘Mr.’” And I always have, although I have more recently had to alter that to “Ms.” or — in most education settings these days — “Dr.”

Marketing, according to Lil: “If someone asks you where something is, don’t lead them to it. Tell them where it is located. As they are going to it, they may look around and find something else to buy.” I spent quite a bit of time interpreting that advice to my own kids, applying it to staying focused and not getting distracted from their goals yada yada yada.

Lil’s attitude toward the girls from the local home for unwed mothers may have influenced my reluctance to risk the consequences of “messing around” in those pre-Pill days. Those temporary residents apparently were allowed to go shopping once a week or so, and they came in groups to Woolworth’s. “Watch those girls,” Lil would admonish me. “They can’t be trusted.” Why can’t they be trusted? I wondered — to myself — I would never argue with Lil. It looked as if maybe they trusted somebody else too much.

“Never stand still,” Lil said. “You aren’t working if you’re standing still.” Lil did allow me to sit still once, however, when I pin-tagged myself instead of the shirt I was pricing. I hit the switch on the machine too soon, so the pin grazed the end of my finger as it stamped the price on my fingernail. I would have fainted if Lil had not been close by. She sat me down and told me to lean over and put my head on my knees. I have used that method ever since to ease sudden lightheadedness. And I have always been able to return and face whatever threw me for a loop because of what Lil said as she applied a Band Aid to my finger: “Feeling better? Okay, get back to work.”

The only time Lil advised me not to work was the Saturday I asked off to go to the senior class picnic. Lil said to come in when I got back to town, and I did, sporting the worst sunburn I ever got. I could barely walk through the door of Woolworth’s, but I was determined to finish out my shift. When Lil saw me, she said, “Go home and take care of that! And don’t ever let yourself sunburn like that again!” I haven’t.

Shortly after that, when I graduated from high school, Lil offered me a forty-hour a week job at Woolworth’s. I was tempted to take it, but my mom’s advice trumped Lillian Stottlemyre: “Evelyn Ann Stogsdill, I will not have you stay around and marry one of these yahoos from Sand Springs. You’re going to college.”

In August, 1964, Lil handed me my last pay envelope. By then, I was drawing a whopping $1.05 an hour, and I actually had managed to save over $400. That, along with a couple of scholarships, was enough to pay for my first year at Northeastern State College in Tahlequah, Oklahoma.

All I really need to know about life — and a college education — provided by Woolworth’s!

[separator type=”thin”]

If you’re one of our faithful readers and you have a story you’d like to share with us, email it to us at editors@dosouthmagazine.com. We’d love to hear from you.