[title subtitle=”words and images: Benita Drew “][/title]

Inside Joe Kremers’ home in Clarksville, Arkansas, there’s a prized collection, down a narrow staircase, housed in a well-lit white room, with a handmade wooden sign reading “Joe’s Bug Lab.” What started in 1957, as a Clarksville High School science project, turned into a collection that’s grown for the past sixty years. Glass jars are carefully placed on shelves lining the walls, and in the middle of the room, from floor to ceiling. His basement houses an impressive collection of insects both common and rare, some to the point of being classified as endangered, as well as a few that no one has yet been able to identify.

Joe’s brother Tom said, “I remember the box (that he started his collection in) from when I was nine years old. Joe ordered pins from somewhere, and I remember thinking I’d never seen pins so tiny. They were made just for that.” Joe added that the box, which he still uses to take a sample of his bugs to show at school visits, was his mother’s sewing box before he claimed it for his first collection.

A professor from Ohio State once spent four hours studying Joe’s collection and left with a list of thirty names. Of those, six were declared to have never been found in the state before, earning Joe recognition in the 2009 Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science. He’s also had visitors from Brigham Young, Mississippi State, and Southern Arkansas University, to name a few.

The group from Brigham Young asked him to come with them while researching crayfish that lived in the mountains. “To me, it was fun just going with the professionals, a bunch of us traipsing through the woods,” Joe said. The information they gathered was included in a book, Crayfish of the World, written by a Swedish man from the group.

One might think he’d devoted his career to these creatures, but that isn’t the case. “I just always liked bugs, even as a little guy,” Joe said. He still had a few from his high school project and added to it when he had another bug-collection assignment while attending the College of the Ozarks. He’d have liked to have made a career out of studying bugs, but times were tough, and he left to work in the coal mines after his first semester.

Joe met his future wife Trenna at a community dance, and they married in 1962. He only had a handful of bugs in his collection at the time but continued to collect.

He bug-hunts when he has time or sets traps, usually consisting of two-liter bottles, with a hole cut in the top and species-specific homemade bait placed inside. “You have to find out what plant they feed on. I just try different stuff for the traps, like maple syrup and sugar. Sometimes I catch one right off, others not. I just try different things until I find what works.” He worked for years to find a sugar maple borer beetle, but then tried beer, sugar and maple syrup and caught eighteen in four days.

He bug-hunts when he has time or sets traps, usually consisting of two-liter bottles, with a hole cut in the top and species-specific homemade bait placed inside. “You have to find out what plant they feed on. I just try different stuff for the traps, like maple syrup and sugar. Sometimes I catch one right off, others not. I just try different things until I find what works.” He worked for years to find a sugar maple borer beetle, but then tried beer, sugar and maple syrup and caught eighteen in four days.

Joe uses approximately forty books, some bought and some gifts, to identify most of his findings, though occasionally he can’t find a specimen in any of his books or on the Internet. That’s when he calls Professor Henry Robison of Southern Arkansas University. “Henry knows everybody. If you’ve got a bug, he knows a bug expert. If you’ve got a frog, he knows a frog expert. The same with moss and fish. If I can’t identify a bug, he sends it to one of his buddies that is a curator at the Smithsonian and an expert on the longhorn beetles, which are my favorite.” His connection with Henry is how the word of his collection got out to other universities across the United States.

Joe not only enjoys sharing his collection with experts but curious children as well. Starting approximately ten years ago with his daughter-in-law Andrea’s second-grade class, he began letting them tour his bug lab. Now each fall, the entire Clarksville second grade files into his room full of bug-filled glass jars and shelves, ten at a time. It takes three days for the approximately 200 students to have a chance to inspect the insects up close.

In the spring, he takes a relatively small sample of his bugs to an event for the Pottsville fifth grade, where his daughter Ann Lee teaches. Approximately 130 children each year learn how to start their own collections and are taken on a field trip, armed with nets, to see who can collect the most specimens.

Of Joe’s six children, twelve grandchildren, and four great-grandchildren, none have yet shown the desire and patience to collect as he has. “The grands will get involved and give up in a week or two,” he said, adding that when he threatens to throw them away, suddenly all of them want to keep them.

While he estimates that ninety-five percent of his collection was found in Arkansas, Trenna recalls an outing in Texas that netted a few more. “He set up a box on top of the car with a funnel to guide them in, and we drove around Texas that way. The kids were kind of embarrassed,” she chuckled.

Tom tells another story. “Joe was clearing land and dug up an elderberry bush. He found larvae in the root. He had one of the bushes growing in his yard, so he drilled a hole in the root of it and put the larvae in it then built a cage over it, so he could catch it when it came out.” Joe said it was an elderberry borer beetle, and that he had built a similar wire device around a white oak to trap a white oak borer beetle. He waited three years for the white oak borer beetle to emerge. Most emerge every other year, while some take up to thirty.

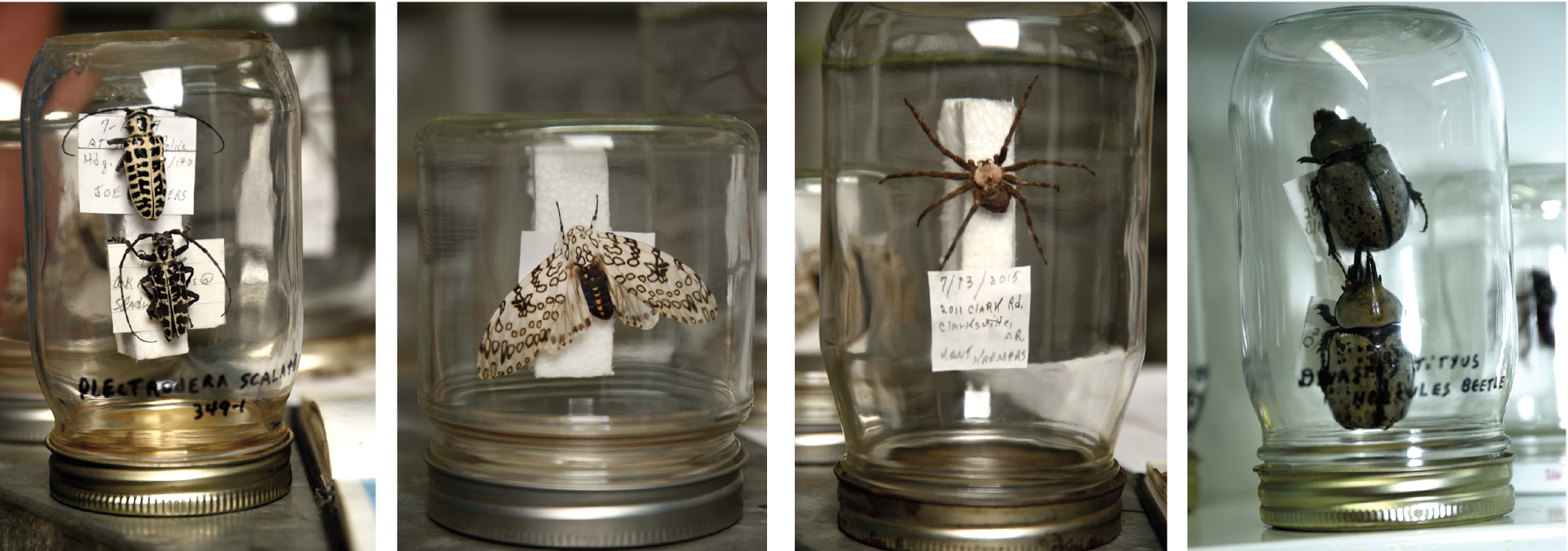

In each of his jars, he has numerous examples of the same insect, pinned to a piece of Styrofoam, with the insect name, where it was found, and if someone gave it to him: that person’s name. He includes a series of numbers: the number that coincides with that particular bug within a book and the number of the book he used to identify the bug. Each of his books has a number taped to the spine for this purpose.

Of his vast collection, he remembers stories about many and has his favorites. The Dryobius Sexnotatus, 103-1, 2012, is one example. He hunted the long black and yellow beetle with antenna longer than its body, for a considerable time. Then, within two months in 2012, he and his friend Gene Leeds found four in Piney Creek and north of Oark. It’s considered for the endangered list for its rarity.

The apple borer beetle, or Saperda Candida, is one he hunted for years. His son Paul found one and brought it to him, as he often does with bugs. Joe admitted he has still not found an apple borer beetle himself.

Looking as well preserved as each of the other specimens, the Plectodera, or cottonwood beetle, still sits on the shelf, a part of his original 1975 collection. Joe also proudly displayed a fish-eating spider which he said he found interesting because it goes underwater to catch minnows.

The key to keeping a collection intact for so long, Joe said, is to dry them well to prevent mold, so he keeps a dehydrator running.

His trove of meticulously preserved insects might not gain him fame or fortune. It has, however, unquestionably gained respect among professionals and fascination from students. Joe shares letters from second graders thanking him for sharing his collection with them, with as much pleasure as he does his books and cards signed by educators and professionals in the study of bugs. Joe is just happy collecting bugs, learning as he goes, and sharing that knowledge with others.